in honor of jan. 16, 1972

I WROTE THE FOLLOWING FOR A PROPOSED MAGAZINE CELEBRATING THE FIRST 50 SUPER BOWLS.

Although the magazine never came out, the story remains vivid.

Before becoming a $4 billion juggernaut (the most valuable team in all of pro sports, according to Forbes), before winning five Super Bowls and before earning the moniker “America’s Team,” the Dallas Cowboys carried a completely different reputation.

They were labeled “Next Year’s Champions.” The name was drenched in sarcasm, a taunting reminder of their ability to get close to the top … and their inability to win the big one.

They lost the play-in game to Super Bowls I and II. They cruised to division titles the next two seasons only to get bounced from the playoffs in the first round both times. They made progress by reaching Super Bowl V, only to undermine it with a brutal performance.

In a game remembered as the Blunder Bowl because of all the turnovers – four by Dallas, seven by Baltimore – the Cowboys gave up 10 points in the final eight minutes to lose 16-13. Their “Doomsday Defense” was so good that linebacker Chuck Howley was named MVP, still the only time the award has gone to a member of the losing team, yet the most indelible image of a Dallas player was Bob Lilly unleashing his rage over the franchise’s ongoing failure by hurling his helmet about 50 yards.

Then it happened.

The Cowboys broke through the next year in 1971, clobbering the Dolphins in Super Bowl VI for their first championship. The Cowboys would play in three more Super Bowls in the 1970s, making their royal-blue star on a silver helmet synonymous with greatness right at the time the NFL’s popularity was exploding. Their coach and quarterback became icons; heck, even their cheerleaders became international sensations. The franchise was on such as roll that they were dubbed “America’s Team” in an NFL Films video wrapping up a season in which they lost the Super Bowl.

Clearly, this was the turning point in Cowboys history. And when you consider how much they became a high tide that lifted all boats in the NFL, you could argue that – as we reach the golden moment of the 50th Super Bowl – the ’71 club was among the most important in league history.

Yet that’s not the only reason this group deserves a closer look. It’s also fun to riding along on one of the wildest, wackiest years for any Super Bowl champion.

They were 4-3 midway through a 14-game season, having even lost to the dreadful Saints. The big problem was that coach Tom Landry couldn’t decide whether to trust incumbent quarterback Craig Morton or backup Roger Staubach. He was so befuddled that he had them spend a game taking turns every play. The same day Landry finally picked one, a star offensive lineman shattered his right leg while showing off on a motorcycle. His replacement came from a commercial real estate office. And, through it all, their star running back wasn’t talking – not to reporters, coaches or most of his teammates.

Yep, the 1971 Cowboys are memorable for all sorts of reasons.

***

On the plane ride home from Super Bowl V in Miami, Landry went to chat with Roger and Marianne Staubach.

Staubach was the only healthy Dallas player who’d suited up for the game but didn’t play. He watched from the sideline as Morton threw three interceptions in the final 8:51, helping a 13-6 lead dissolve into a 16-13 loss.

A few weeks shy of 29, Staubach was coming off only his second season in the NFL, his career delayed by a commitment to the Navy. He knew the clock was ticking on his prime years.

The former Heisman Trophy winner wanted a chance, but wondered if he’d get it in Dallas. After all, Morton was both younger (by a year; they share a birthday) and more experienced. He’d spent four years as Don Meredith’s understudy before his two years starting ahead of Staubach. Morton won division titles both seasons and, despite the sorry finish in the Super Bowl, he had just led the club within a few minutes of a title. Landry found comfort in Morton’s knowledge and experience.

Morton knew Staubach threatened his job security. When he hurt his throwing shoulder in 1969, he played through it. His workaround was a new motion, although that only led to more pain. He came away from the Super Bowl scheduled for an operation to relieve a pinched nerve and remove bone chips in his elbow.

With all that as the backdrop, Landry made his way to Staubach on the airplane, sat down and said: “You’ve got to be ready to compete for the starting job. I think you can make your move this coming year – if you’re ever going to make it.”

***

Before Morton’s arm recovered, his reputation took a beating.

He got arrested for public urination, filed for bankruptcy and endured the revelation that he’d called a hypnotist before every game the previous season. The New York Times asked NFL coaches to pick any quarterback other than their own for the ’71 season; of the 22 anonymous responders, none picked the 28-year-old starter from the most recent Super Bowl. (Morton also penned a guest column in a Dallas newspaper. The headline: “The Best Is Yet To Come.”)

Staubach was the family man who’d served his country, and his offseason headlines were for things like asking locals to fly flags to support prisoners of war, giving a speech at the Salvation Army, hosting a football camp for kids, and being a guest speaker for a town’s Religious Heritage Day during a time when that was considered quaint, not controversial. (His offseason wasn’t all great. About 10 months after his dad died, his wife delivered a stillborn daughter. There was a funeral and lots of tears from their other three daughters.)

Once the duo got on the field for training camp and preseason, the competition remained close. Finally, on the first Monday of the regular season, Landry chose …

Both.

Staubach was to start the opener. But he was hurt, so Morton got the nod.

And so it went for six maddening weeks. While sentiment was building for Staubach – especially among teammates, who liked his leadership and quick feet – Landry felt more comfortable with the less-mobile, more-predictable Morton.

Going into a Halloween game in Chicago, Landry made his most bizarre move yet: a “quarterback shuttle” in which Morton and Staubach would alternate snaps. It didn’t totally work out that way, though, as Landry stuck with Morton late in the second quarter and through most of the fourth on the way to a 23-19 loss.

“I’m back to where I was the year before,” Staubach thought. “Craig is going to be the quarterback.”

***

The next day, with Landry realizing he needed to pick a single quarterback, a crew of players met to indulge in their new favorite hobby – riding dirt bikes.

The regulars included Lilly, Mike Ditka, Walt Garrison, Dan Reeves, Cliff Harris, Charlie Waters and Mike Edwards. This time, Ralph Neely showed up with his own new toy … and a poor understanding of how to use it.

On his final spin of the day, the guy nicknamed “Rotten” for his sour disposition soared about 20 feet off an incline. When the bike came down, Neely failed to use the foot pegs to cushion the blow. He slammed his feet into the ground, breaking his right leg in three places. So much for protecting the quarterback’s blind side with a member of the NFL’s all-decade team for the 1960s.

(The group agreed to tell Landry that they’d been riding horses when a snake bit Neely’s horse, spooking the animal and throwing the lineman. Reeves was chosen to break the news because he was a player-coach. Other circumstances prompted them to scuttle that plan.)

After getting Neely to a hospital, the guys cleaned up and met the rest of the team for a Las Vegas Night event hosted by the wives’ club. Among the guests was Tony Liscio, who’d been the starting left tackle from 1966 until Neely replaced him midway through 1970.

Liscio had been traded to San Diego in the offseason, then traded again to Miami. He retired instead of reporting and returned to Dallas to sell commercial real estate. At the party, Edwards half-jokingly told him to be ready in case Landry called.

Elsewhere at the party, offensive assistant coach Ray Renfro pulled aside Staubach with a secret: Landry picked him to be the starter. Staubach shared this with only one person, Marianne.

“I am going to finish the season,” he told her, “or it’s going to finish my career.”

***

Sure enough, everything clicked.

With Staubach entrenched at quarterback – and, a week later, Liscio at left tackle – the Cowboys became unstoppable.

They pulled out a tight game on the road against the Cardinals. They shut out the Redskins in D.C. They beat the Rams on Thanksgiving and ruined Joe Namath’s return from a year-plus injury absence by crushing the Jets.

The Cowboys went 7-0 after Staubach took over, winning the division title for a sixth straight season.

They opened the playoffs in Minnesota, a battle of their No. 1 offense against the Vikings’ No. 1 defense. Dallas won, then returned home to play San Francisco in the NFC Championship game. It was a rematch of the previous year’s game, and the result was the same. The Cowboys were headed back to the Super Bowl – only this time, with a new quarterback.

***

Before Super Bowl V, running back Duane Thomas offered one of the most memorable lines in the game’s history. Asked about playing in the ultimate game, he said, “Then why are they playing it again next year?”

Thomas and the Cowboys were indeed there again. And for Thomas, what a long, strange trip it was between games.

After being named rookie of the year in 1970, he retired. He wanted more money. Even Jim Brown got involved. Thomas ended up showing up at team president Tex Schramm’s office a few days before the opener. Yet his bitterness lingered, manifesting mostly in silence and stares. Landry avoided further confrontation by allowing Thomas to play by a different set of rules, a double-standard that irked others.

“It was tense, like walking on eggshells,” said Reeves, who was both a running back and coach of the running backs. “You’re trying to get your group ready, and he wouldn’t speak to anybody.”

Long before Marshawn Lynch turned surliness into a Super Bowl sideshow, Thomas did exactly that during Media Day for Super Bowl VI. His only utterance was, “What time is it?”

***

By January 1972, the Super Bowl had become a big deal. Nothing like it is today, of course, but a quantum leap beyond its origins just six years before, when the game didn’t even sell out the L.A. Coliseum.

Super Bowl V was watched by an estimated 46 million people, the biggest audience for a scheduled program in four years and the most ever for a sporting event. Put another way, three of every four televisions turned on that afternoon were watching.

Hopes were high that Super Bowl VI – between the Cowboys and Miami Dolphins – might take things up a notch.

The game was played in New Orleans, outdoors at Tulane Stadium. Four Air Force jets that were supposed to arrive during the national anthem showed up a few minutes late. Maybe the weather was to blame; it was 39 degrees at kickoff, still the coldest ever.

The Cowboys were more than ready. They had the experience of being there before and a hunger to finish what they’d started. Landry’s pregame speech was simply, “We’ve got a ball game to play. You know what to do. Go do it.”

The Dolphins showed some jitters on their second drive. Bob Griese handed off to Larry Csonka and Csonka never wrapped it up. After 235 carries all season and postseason without a fumble, he coughed up the ball without being hit.

The game’s most memorable play came on Miami’s next possession.

Facing third-and-9 from his own 38, Griese dropped back to pass … and kept dropping back. When he saw Larry Cole charging from his right, Griese tried going left, only to discover Lilly coming right at him. So Griese headed back toward his end zone, still holding out hope of getting off the pass. He didn’t. Lilly sacked him for a loss of 29 yards.

Despite thoroughly outplaying Miami, Dallas led only 10-3 at halftime. While Ella Fitzgerald, Carol Channing and others performed a tribute to the recently deceased Louis Armstrong, Landry made the adjustments that would turn this game into a rout.

The Cowboys won 24-3, playing nearly a perfect game. The offense was efficient, the defense fantastic. It remains the fewest points allowed in a Super Bowl, and the only time a team was held without a touchdown. A key point to remember is that Dallas did this against a Miami team that would go undefeated the next season, and would win the next two Super Bowls.

As the final seconds counted down, Morton went to Landry, shook his hand and said, “I’m really happy for you.”

Lilly, Garrison, Rayfield Wright and John Niland lifted Landry onto their shoulders for a ceremonial ride. His smile from that lofty viewpoint was so memorable that Staubach recalled it at Landry’s memorial service in 2000.

Lilly ran into the locker room and leaped with joy. Soon, he needed a match. The victory cigar that he’d brought with him to Super Bowl V, then kept in a freezer all year, was finally ready to be lit.

“They can’t say we don’t win the big one anymore,” Schramm said.

Thomas ran 19 times for 95 yards and a touchdown, and caught three passes for 17 more yards. He could’ve been named MVP, but the powers-that-be likely feared what he might do in the presentation ceremony. So they gave it to Staubach. Offered a sports car, he took a station wagon instead. Thomas, meanwhile, never carried the ball again for Dallas.

***

The ’71 Cowboys were not destiny’s darlings, some gilded group that everyone just knew was going to come out on top.

They become champions the hard way, even if many of the challenges they overcame were of their own making.

Given the benefit of four-plus decades of hindsight, we find a team that stacks up … well, maybe not among the upper-eschelon of champs, but higher on the list than you might expect. Consider:

In 2010, as part of the buildup to the first Super Bowl held in North Texas, organizers asked fans to rank the 100 greatest moments in the first 100 years of football in the region. The 1971 Cowboys topped them all.

That may be a bit lofty. After all, most observers consider the ’77 Cowboys to be Staubach’s greatest team, and of course the 1992, ’93 and ’95 clubs led by Troy Aikman, Emmitt Smith and Michael Irvin were pretty darn special.

But here’s the thing that underscores the importance of this group: They turned the Cowboys into THE COWBOYS. Not directly, mind you, but this was the U-turn on the road from “Next Year’s Champions” to “America’s Team.”

This was the season when Tom Landry shed his label as the coach who couldn’t win the big one, when Roger Staubach added to the football fairy tale he’d begun at Navy and in the Navy, and when a nation blossoming as football fans began to appreciate the collection of stars wearing blue stars on their helmets. Their core fans were finally rewarded for their faith; within a few years, everyone would love ‘em or hate ‘em … love, mostly.

“I don’t care how many Super Bowls you win, the first one is the most important,” linebacker Lee Roy Jordan said a few years ago. “Until you get that first one, you’re just another team.”

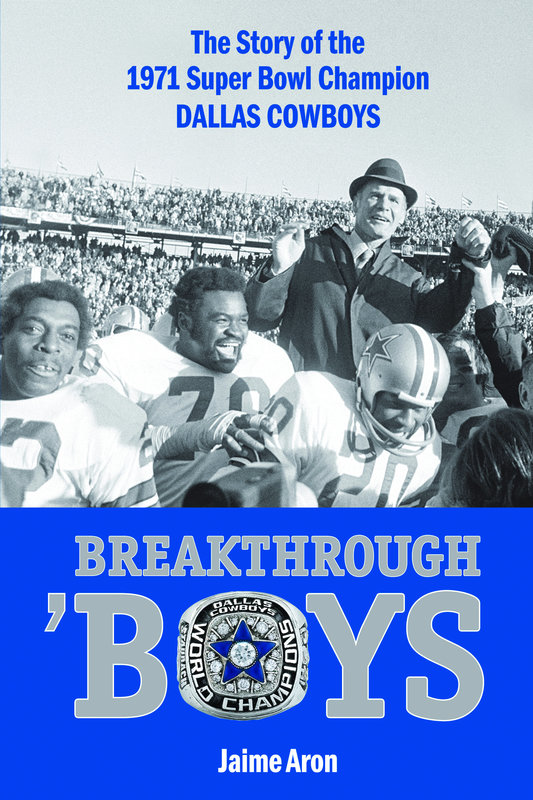

Jaime Aron is author of “Breakthrough ‘Boys: The Story of the 1971 Dallas Cowboys,” as well as “Dallas Cowboys: The Complete Illustrated History” and “I Remember Tom Landry.” He covered the team for 13 years as Texas Sports Editor for The Associated Press.

They were labeled “Next Year’s Champions.” The name was drenched in sarcasm, a taunting reminder of their ability to get close to the top … and their inability to win the big one.

They lost the play-in game to Super Bowls I and II. They cruised to division titles the next two seasons only to get bounced from the playoffs in the first round both times. They made progress by reaching Super Bowl V, only to undermine it with a brutal performance.

In a game remembered as the Blunder Bowl because of all the turnovers – four by Dallas, seven by Baltimore – the Cowboys gave up 10 points in the final eight minutes to lose 16-13. Their “Doomsday Defense” was so good that linebacker Chuck Howley was named MVP, still the only time the award has gone to a member of the losing team, yet the most indelible image of a Dallas player was Bob Lilly unleashing his rage over the franchise’s ongoing failure by hurling his helmet about 50 yards.

Then it happened.

The Cowboys broke through the next year in 1971, clobbering the Dolphins in Super Bowl VI for their first championship. The Cowboys would play in three more Super Bowls in the 1970s, making their royal-blue star on a silver helmet synonymous with greatness right at the time the NFL’s popularity was exploding. Their coach and quarterback became icons; heck, even their cheerleaders became international sensations. The franchise was on such as roll that they were dubbed “America’s Team” in an NFL Films video wrapping up a season in which they lost the Super Bowl.

Clearly, this was the turning point in Cowboys history. And when you consider how much they became a high tide that lifted all boats in the NFL, you could argue that – as we reach the golden moment of the 50th Super Bowl – the ’71 club was among the most important in league history.

Yet that’s not the only reason this group deserves a closer look. It’s also fun to riding along on one of the wildest, wackiest years for any Super Bowl champion.

They were 4-3 midway through a 14-game season, having even lost to the dreadful Saints. The big problem was that coach Tom Landry couldn’t decide whether to trust incumbent quarterback Craig Morton or backup Roger Staubach. He was so befuddled that he had them spend a game taking turns every play. The same day Landry finally picked one, a star offensive lineman shattered his right leg while showing off on a motorcycle. His replacement came from a commercial real estate office. And, through it all, their star running back wasn’t talking – not to reporters, coaches or most of his teammates.

Yep, the 1971 Cowboys are memorable for all sorts of reasons.

***

On the plane ride home from Super Bowl V in Miami, Landry went to chat with Roger and Marianne Staubach.

Staubach was the only healthy Dallas player who’d suited up for the game but didn’t play. He watched from the sideline as Morton threw three interceptions in the final 8:51, helping a 13-6 lead dissolve into a 16-13 loss.

A few weeks shy of 29, Staubach was coming off only his second season in the NFL, his career delayed by a commitment to the Navy. He knew the clock was ticking on his prime years.

The former Heisman Trophy winner wanted a chance, but wondered if he’d get it in Dallas. After all, Morton was both younger (by a year; they share a birthday) and more experienced. He’d spent four years as Don Meredith’s understudy before his two years starting ahead of Staubach. Morton won division titles both seasons and, despite the sorry finish in the Super Bowl, he had just led the club within a few minutes of a title. Landry found comfort in Morton’s knowledge and experience.

Morton knew Staubach threatened his job security. When he hurt his throwing shoulder in 1969, he played through it. His workaround was a new motion, although that only led to more pain. He came away from the Super Bowl scheduled for an operation to relieve a pinched nerve and remove bone chips in his elbow.

With all that as the backdrop, Landry made his way to Staubach on the airplane, sat down and said: “You’ve got to be ready to compete for the starting job. I think you can make your move this coming year – if you’re ever going to make it.”

***

Before Morton’s arm recovered, his reputation took a beating.

He got arrested for public urination, filed for bankruptcy and endured the revelation that he’d called a hypnotist before every game the previous season. The New York Times asked NFL coaches to pick any quarterback other than their own for the ’71 season; of the 22 anonymous responders, none picked the 28-year-old starter from the most recent Super Bowl. (Morton also penned a guest column in a Dallas newspaper. The headline: “The Best Is Yet To Come.”)

Staubach was the family man who’d served his country, and his offseason headlines were for things like asking locals to fly flags to support prisoners of war, giving a speech at the Salvation Army, hosting a football camp for kids, and being a guest speaker for a town’s Religious Heritage Day during a time when that was considered quaint, not controversial. (His offseason wasn’t all great. About 10 months after his dad died, his wife delivered a stillborn daughter. There was a funeral and lots of tears from their other three daughters.)

Once the duo got on the field for training camp and preseason, the competition remained close. Finally, on the first Monday of the regular season, Landry chose …

Both.

Staubach was to start the opener. But he was hurt, so Morton got the nod.

And so it went for six maddening weeks. While sentiment was building for Staubach – especially among teammates, who liked his leadership and quick feet – Landry felt more comfortable with the less-mobile, more-predictable Morton.

Going into a Halloween game in Chicago, Landry made his most bizarre move yet: a “quarterback shuttle” in which Morton and Staubach would alternate snaps. It didn’t totally work out that way, though, as Landry stuck with Morton late in the second quarter and through most of the fourth on the way to a 23-19 loss.

“I’m back to where I was the year before,” Staubach thought. “Craig is going to be the quarterback.”

***

The next day, with Landry realizing he needed to pick a single quarterback, a crew of players met to indulge in their new favorite hobby – riding dirt bikes.

The regulars included Lilly, Mike Ditka, Walt Garrison, Dan Reeves, Cliff Harris, Charlie Waters and Mike Edwards. This time, Ralph Neely showed up with his own new toy … and a poor understanding of how to use it.

On his final spin of the day, the guy nicknamed “Rotten” for his sour disposition soared about 20 feet off an incline. When the bike came down, Neely failed to use the foot pegs to cushion the blow. He slammed his feet into the ground, breaking his right leg in three places. So much for protecting the quarterback’s blind side with a member of the NFL’s all-decade team for the 1960s.

(The group agreed to tell Landry that they’d been riding horses when a snake bit Neely’s horse, spooking the animal and throwing the lineman. Reeves was chosen to break the news because he was a player-coach. Other circumstances prompted them to scuttle that plan.)

After getting Neely to a hospital, the guys cleaned up and met the rest of the team for a Las Vegas Night event hosted by the wives’ club. Among the guests was Tony Liscio, who’d been the starting left tackle from 1966 until Neely replaced him midway through 1970.

Liscio had been traded to San Diego in the offseason, then traded again to Miami. He retired instead of reporting and returned to Dallas to sell commercial real estate. At the party, Edwards half-jokingly told him to be ready in case Landry called.

Elsewhere at the party, offensive assistant coach Ray Renfro pulled aside Staubach with a secret: Landry picked him to be the starter. Staubach shared this with only one person, Marianne.

“I am going to finish the season,” he told her, “or it’s going to finish my career.”

***

Sure enough, everything clicked.

With Staubach entrenched at quarterback – and, a week later, Liscio at left tackle – the Cowboys became unstoppable.

They pulled out a tight game on the road against the Cardinals. They shut out the Redskins in D.C. They beat the Rams on Thanksgiving and ruined Joe Namath’s return from a year-plus injury absence by crushing the Jets.

The Cowboys went 7-0 after Staubach took over, winning the division title for a sixth straight season.

They opened the playoffs in Minnesota, a battle of their No. 1 offense against the Vikings’ No. 1 defense. Dallas won, then returned home to play San Francisco in the NFC Championship game. It was a rematch of the previous year’s game, and the result was the same. The Cowboys were headed back to the Super Bowl – only this time, with a new quarterback.

***

Before Super Bowl V, running back Duane Thomas offered one of the most memorable lines in the game’s history. Asked about playing in the ultimate game, he said, “Then why are they playing it again next year?”

Thomas and the Cowboys were indeed there again. And for Thomas, what a long, strange trip it was between games.

After being named rookie of the year in 1970, he retired. He wanted more money. Even Jim Brown got involved. Thomas ended up showing up at team president Tex Schramm’s office a few days before the opener. Yet his bitterness lingered, manifesting mostly in silence and stares. Landry avoided further confrontation by allowing Thomas to play by a different set of rules, a double-standard that irked others.

“It was tense, like walking on eggshells,” said Reeves, who was both a running back and coach of the running backs. “You’re trying to get your group ready, and he wouldn’t speak to anybody.”

Long before Marshawn Lynch turned surliness into a Super Bowl sideshow, Thomas did exactly that during Media Day for Super Bowl VI. His only utterance was, “What time is it?”

***

By January 1972, the Super Bowl had become a big deal. Nothing like it is today, of course, but a quantum leap beyond its origins just six years before, when the game didn’t even sell out the L.A. Coliseum.

Super Bowl V was watched by an estimated 46 million people, the biggest audience for a scheduled program in four years and the most ever for a sporting event. Put another way, three of every four televisions turned on that afternoon were watching.

Hopes were high that Super Bowl VI – between the Cowboys and Miami Dolphins – might take things up a notch.

The game was played in New Orleans, outdoors at Tulane Stadium. Four Air Force jets that were supposed to arrive during the national anthem showed up a few minutes late. Maybe the weather was to blame; it was 39 degrees at kickoff, still the coldest ever.

The Cowboys were more than ready. They had the experience of being there before and a hunger to finish what they’d started. Landry’s pregame speech was simply, “We’ve got a ball game to play. You know what to do. Go do it.”

The Dolphins showed some jitters on their second drive. Bob Griese handed off to Larry Csonka and Csonka never wrapped it up. After 235 carries all season and postseason without a fumble, he coughed up the ball without being hit.

The game’s most memorable play came on Miami’s next possession.

Facing third-and-9 from his own 38, Griese dropped back to pass … and kept dropping back. When he saw Larry Cole charging from his right, Griese tried going left, only to discover Lilly coming right at him. So Griese headed back toward his end zone, still holding out hope of getting off the pass. He didn’t. Lilly sacked him for a loss of 29 yards.

Despite thoroughly outplaying Miami, Dallas led only 10-3 at halftime. While Ella Fitzgerald, Carol Channing and others performed a tribute to the recently deceased Louis Armstrong, Landry made the adjustments that would turn this game into a rout.

The Cowboys won 24-3, playing nearly a perfect game. The offense was efficient, the defense fantastic. It remains the fewest points allowed in a Super Bowl, and the only time a team was held without a touchdown. A key point to remember is that Dallas did this against a Miami team that would go undefeated the next season, and would win the next two Super Bowls.

As the final seconds counted down, Morton went to Landry, shook his hand and said, “I’m really happy for you.”

Lilly, Garrison, Rayfield Wright and John Niland lifted Landry onto their shoulders for a ceremonial ride. His smile from that lofty viewpoint was so memorable that Staubach recalled it at Landry’s memorial service in 2000.

Lilly ran into the locker room and leaped with joy. Soon, he needed a match. The victory cigar that he’d brought with him to Super Bowl V, then kept in a freezer all year, was finally ready to be lit.

“They can’t say we don’t win the big one anymore,” Schramm said.

Thomas ran 19 times for 95 yards and a touchdown, and caught three passes for 17 more yards. He could’ve been named MVP, but the powers-that-be likely feared what he might do in the presentation ceremony. So they gave it to Staubach. Offered a sports car, he took a station wagon instead. Thomas, meanwhile, never carried the ball again for Dallas.

***

The ’71 Cowboys were not destiny’s darlings, some gilded group that everyone just knew was going to come out on top.

They become champions the hard way, even if many of the challenges they overcame were of their own making.

Given the benefit of four-plus decades of hindsight, we find a team that stacks up … well, maybe not among the upper-eschelon of champs, but higher on the list than you might expect. Consider:

- They won their final 10 games (regular season and postseason), and did so quite dominantly. They never trailed by more than a touchdown in any of those games. And while Staubach steadied the offense, Doomsday truly led the way. Dallas allowed only 18 points the entire postseason; among Super Bowl champions, only the ’85 Bears allowed less (10).

- Of the 22 Super Bowl starters, 10 are in either the Pro Football Hall of Fame or the Cowboys’ Ring of Honor.

- All told, the roster featured nine future Hall of Famers: Herb Adderley, Lance Alworth, Ditka, Forrest Gregg, Bob Hayes, Lilly, Mel Renfro, Staubach and Wright. The number swells to 11 with Landry and Schramm.

In 2010, as part of the buildup to the first Super Bowl held in North Texas, organizers asked fans to rank the 100 greatest moments in the first 100 years of football in the region. The 1971 Cowboys topped them all.

That may be a bit lofty. After all, most observers consider the ’77 Cowboys to be Staubach’s greatest team, and of course the 1992, ’93 and ’95 clubs led by Troy Aikman, Emmitt Smith and Michael Irvin were pretty darn special.

But here’s the thing that underscores the importance of this group: They turned the Cowboys into THE COWBOYS. Not directly, mind you, but this was the U-turn on the road from “Next Year’s Champions” to “America’s Team.”

This was the season when Tom Landry shed his label as the coach who couldn’t win the big one, when Roger Staubach added to the football fairy tale he’d begun at Navy and in the Navy, and when a nation blossoming as football fans began to appreciate the collection of stars wearing blue stars on their helmets. Their core fans were finally rewarded for their faith; within a few years, everyone would love ‘em or hate ‘em … love, mostly.

“I don’t care how many Super Bowls you win, the first one is the most important,” linebacker Lee Roy Jordan said a few years ago. “Until you get that first one, you’re just another team.”

Jaime Aron is author of “Breakthrough ‘Boys: The Story of the 1971 Dallas Cowboys,” as well as “Dallas Cowboys: The Complete Illustrated History” and “I Remember Tom Landry.” He covered the team for 13 years as Texas Sports Editor for The Associated Press.

|

www.JaimeAron.com

|